Dropping drop coverage

Damian Lillard and the folly of finding the "right" way to defend a 38-footer.

Hello! In case you didn’t see it, I’m writing a book about NBA Xs and Os that’ll be out Spring 2022. The topic is basically the same as the goal of this newsletter: to help you, a normal basketball fan, understand and appreciate the strategies and tactics of this beautiful game. Thanks to Clarissa Young and everyone else at Triumph Books for taking on a project that boils down to “write a book about the very mission of your entire professional career.”

If you have a few minutes, I could use your help filling out this survey. It’ll help me know what you folks actually want to know more about. Thank you for your continued support!

Damian Lillard and the Portland Trail Blazers are on the run of a lifetime. After rallying to make the NBA Playoffs, they stole Game 1 from the heavily favored Lakers on Tuesday. While Lillard scored “only” 34 points in this game, he did produce the most cold-blooded shot of the season.

That was classified as a 35-footer, but it looked and felt even longer. It was the same pull-up jumper every point guard now has in their bag, except from half court. It came late in the fourth quarter of a tie game in the playoffs, and Portland never relinquished the lead thereafter.

It also triggered an interesting discussion with many of my fellow Xs and Os enthusiasts. Yes, the shot was incredible. We’re witnessing greatness. At the same time, didn’t the Lakers’ defense screw up in letting Lillard get that clean a look?

My good friend Mo Dakhil says yes.

I jumped in, a bunch of other people jumped in, and we collectively flooded too much of your timelines. Nobody (except Paul George) doubts Lillard’s range, but this wasn’t the first logo three he’s ever taken in his life. He shoots a high percentage on similar looks and just spent two weeks plunging daggers into opponents’ chests with it. With all that in mind, shouldn’t Anthony Davis come up higher to stop the shot?

Mo and others said yes. I (and others) said that was an unfair standard to uphold. They agreed, but it’s the playoffs and the playoffs are hard as shit. I (and others) said that we’re losing sight of Lillard’s brilliance if we focus too much on the granularity of Davis’ positioning. Around in circles we went.

So who’s right? Me, of course. (Just kidding … or am I?). But the real answer is that we were having several separate, related discussions blended into one.

Should the Lakers change their defensive strategy?

Is it really fair to blame them for not executing properly?

Are we really gonna focus on this instead of appreciating Damian Lillard’s range?

Once you tackle each separately, you realize how difficult a conversation this really is.

The gameplan

How do you defend a puzzle like Damian Lillard? The most accurate answer is to mix coverages up so he can’t lock in on any specific one, but even fluid plans needs foundations. All else being equal, what is the default approach and why? What must we take away from Lillard first?

Pick-and-roll defense is complicated, with tons of variations and many more differences in terminology. (This 2014 piece by Doug Eberhardt holds up well while still only reaching the tip of the iceberg). But in the NBA at least, teams generally choose between the following approaches:

Drop: The on-ball defender fights through the screen while the screener’s man drops back to protect the basket. (ICE, or “Blue,” is the sideline version).

Level/Centerfield/etc.: Bring the screener’s man up to the level of the screen, but not past it. (There’s no great catch-all name for this – “catch,” in fact, is one term often used. I think of it as a much smaller drop).

Show/Blitz/Trap/Hedge: All different variations of the same idea: the screener’s man jumps out above the screen to double-team the ball-handler. That can be to buy time for the on-ball defender to recover (as in show/hedge) or to pressure the ball-handler with an actual double team.

Under: The on-ball defender ducks under the screen, intending to meet his man on the other side.

Switch: Pretty self explanatory.

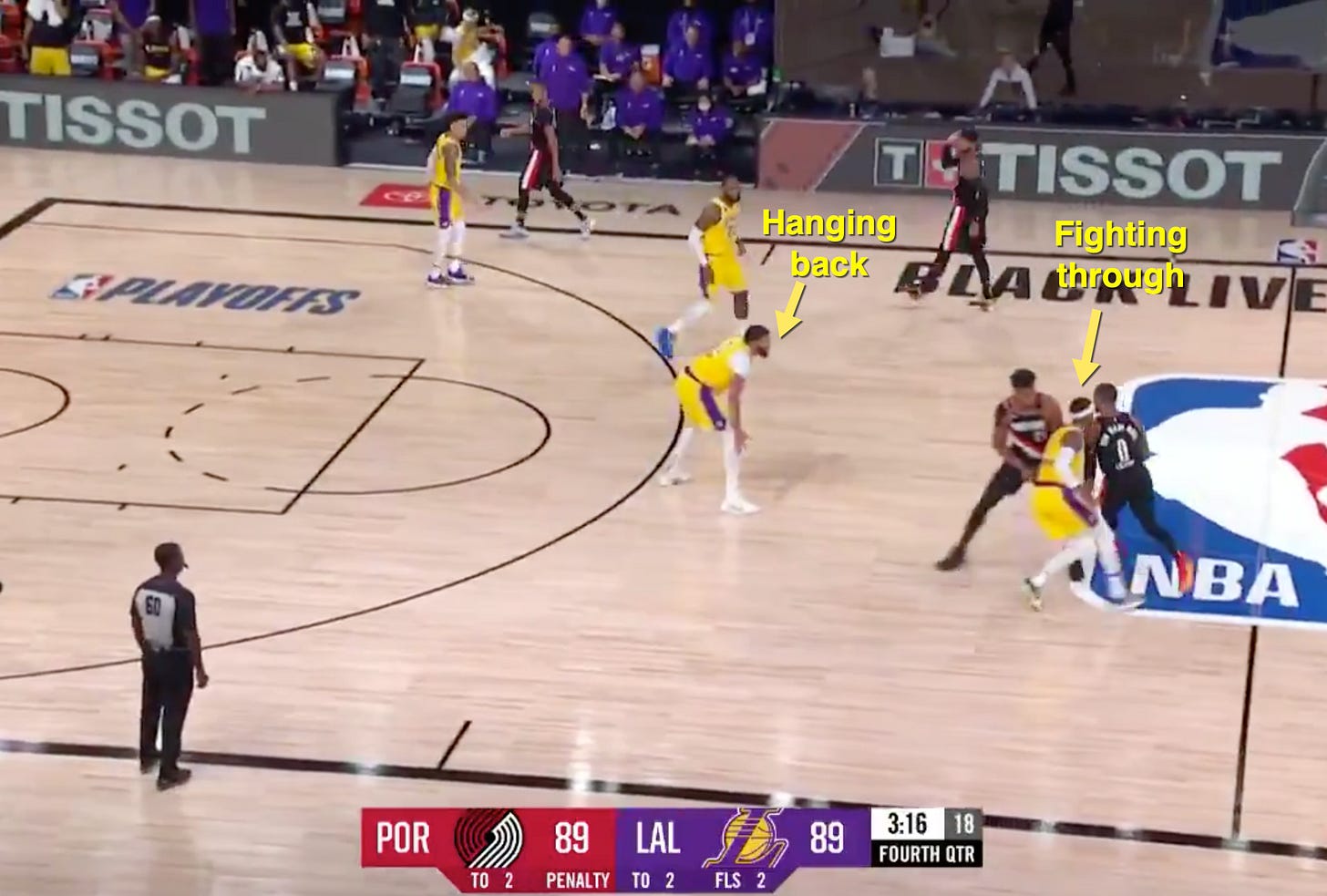

The Lakers appear to be in a drop coverage on this play. Kentavious Caldwell-Pope is fighting through Hassan Whiteside’s screen, while Davis is hanging back.

This is a sensible strategy against many players, but not against Lillard. The numbers at least seem unequivocal.

It’s not hard to understand why. Dropping the big man back opens up the worst of all worlds. Not only does the defense yield space to an elite pull-up long range shooter, but it also gives him space to put a slower defender on skates with his vicious hesitation dribble. It’s how Lillard can put Kristaps Porzingis in the blender in two different ways.

So drop coverage is no bueno. Lillard’s unmatched* accuracy from Logoville is that dangerous. (This is not the place to have the Stephen Curry discussion. Let’s just attach the asterisk and move on).

So what other options do the Lakers have?

Going under is not happening because hahahahahaha of course not. Switching is doable, but challenging. Even if Davis could hang with Lillard one-on-one, asking Caldwell-Pope to keep Whiteside or Jusuf Nurkic off the glass is impractical. That also assuming the Lakers execute the switch perfectly, because if not, Portland will short-circuit it with a quick drive (in Lillard’s case) or slip (in the big man’s case). Getting level to the screen is the best answer in theory, but the hardest in practice for reasons we’ll discuss shortly.

That leaves one final option: trap Lillard and make anyone else beat you, even if they get a man advantage to do it. Sensible? Sure. Lillard is that scary, especially during Dame Time. The talent gap between him and the other four players is arguably such that your three can at least make their eventual shot challenging. Plus, you can sleep easier knowing you did everything in your power to make sure the guy at the top of the scouting report didn’t beat you. (I’ll give Mo this: he’s at least has been consistent with this view. Fast forward to the 1:15:00 mark of our playoff preview podcast).

So then what about this play a couple minutes later?

This is more an apples-to-pears comparison than a perfect one. That trap occurred because Kyle Kuzma was involved in the initial screening action, not Davis. AD switching or dropping on Lillard is one thing. Kuzma is another.

But this is the downside of trapping Lillard. Congratulations! Dame didn’t beat you. Instead, you gave up a catch-and-shoot three to Gary Trent Jr., who has missed like two of those since bubble play started. Lillard’s bomb may have been a psychological blow, but that Trent three counts for the same number of points and dug you a deeper hole with far less time to play. Funny, I didn’t see the same energy about bad Lakers defense after that shot.

I’m being a bit obtuse. It’s entirely fair to say that Trent shot was a tougher look than Lillard’s 35-footer. Make or miss league, etc. But it also wasn’t the only time the Lakers looked silly after trapping Lillard.

Those may be bad traps, but why doesn’t the same logic apply to drop coverage?

The Second Spectrum stats are useful tools, but there are also tons of variables that affect the sample. How many of those drops were with the Lakers’ personnel? How many were with that Blazers closing lineup, which played a total of 25 minutes together in the regular season? Do the stats change depending on how far the bigs drop? Who is Portland’s screener? How well does Lillard’s own man contest from behind on these drops? How does the dropping big man’s size, speed, wingspan, standing reach, pregame meal, and/or sleep schedule affect the results? Am I going to keep asking annoying questions for eternity?

The point is that every choice has consequences. It’s easy to shout about the folly of drop coverage against Lillard. It’s a lot harder to suggest an alternative, much less measure it.

And that’s before we get to …

Putting theory into practice

Question for you, dear reader. What’s the Lakers’ pick-and-roll coverage on this play?

Markieff Morris is up at the level of the ball, something Davis supposedly didn’t do. Alex Caruso is digging into Lillard and will eventually get over the screen. This is how you’re supposed to play Lillard, right?

Yet the play fails because of something Lillard notices in an instant that’s hard to see in real time. As he shifts his body weight down to make his move, he spots Morris leaning slightly to his left. I can only guess the neurons firing in Morris’ brain, but I suspect he’s responding to Lillard’s tendency to cross over and drive away from the screen. To Morris, this body position is a tell for that move. He wants to be ready for it.

You’ve seen the GIF, so you know Morris was wrong. Lillard wanted Morris to think he was coming back middle, but he was planning to use the screen after all. Now Morris is out of the play.

Though Caruso does well to get over Nurkic’s pick and force Lillard into a contested stepback jumper, the Lakers have already lost the sequence. Lillard saw the Lakers’ attempts to bring a big man level to the screen, responded, and got where he wanted to get a shot off. He used his own tendency to go against his normal tendency to go to his normal tendency after all. If your head is spinning reading that last sentence, imagine being Markieff Morris.

Speaking of Morris, let’s fast forward three minutes. Remember that Morris already got beat to the sideline because he covered the middle too quickly. What’s the Lakers’ coverage plan here?

The answer is to trap, but it sure doesn’t look like it. For starters, there’s a moment of confusion on the opposite side between Morris and LeBron James. Morris turns his head to hear instructions, a cue Lillard no doubt noticed.

But the real action happens a beat later. As soon as Morris took LeBron’s instructions, he took a straight first step rather than go diagonally to Lillard. He wasn’t going to get beat to the sideline again.

Good adjustment! Except … Lillard anticipated that and changed his plan. Forget going right. Better to just attack down the chute if Morris is going to take that step away. By the time Morris spots his error, it’s too late. Lillard has zipped by him and Caruso and has an easy lane to finish.

This is Chess Master Dame at work. In his best moments, he’s a game theory manipulator masquerading as a basketball player. If you reveal any cue that tips off your pick-and-roll coverage, he’ll make it look like another one entirely.

That’s especially important to remember when imploring Blazers opponents to get up on Lillard instead of dropping back and surrendering an open pull-up jumper. Knowing the appropriate pick-and-roll scheme is one thing. Implementing it without tipping your hand to the closest thing this league has to a mind reader is another one entirely. If it’s this hard for us analysts to spot the cues Lillard notices, imagine a player trying to do it in real time.

That brings us back to that 35-foot bomb. It’s true that Davis is dropped way back at the moment Lillard releases the shot.

To understand why Davis is back that far, we must rewind and see the play through Lillard’s eyes. A number of folks objected when I tweeted that Lillard’s three was off a “scramble situation.” While this wasn’t obvious chaos, I stand by my definition.

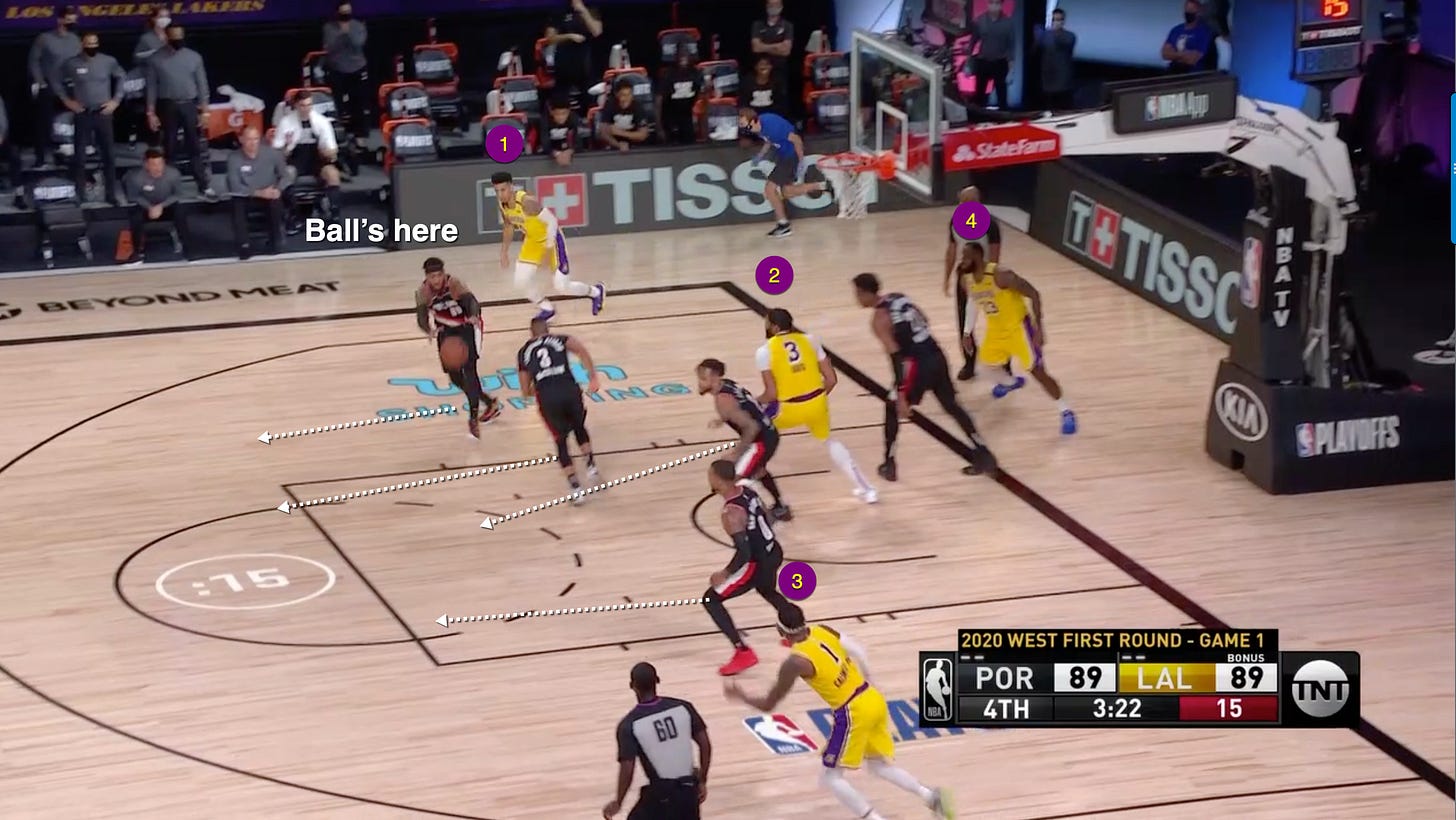

Remember how the Blazers got the ball in the first place. The Lakers were the team going downhill in transition. Two shooters ran to the corners, Davis came up for a ball screen, and LeBron charged from behind with plenty of space to surge to the hoop. This was the Lakers’ elite transition offense at work. They were successfully running without running.

Then, Whiteside swatted LeBron’s layup. As the ball bounced to Portland, the Lakers’ floor balance looked like this.

Four Lakers are behind the ball, which is a recipe for disaster. They knew they had to haul their asses back to prevent Portland from running back at them. That goes double for Davis. He’s the tallest player on the court, and 27 years of basketball training have conditioned him to build a wall around the basket first and then fan out to shooters. That heuristic tends to push through during your 37th minute of a tied playoff opener in an unfamiliar atmosphere.

Damian Lillard knew all that, too. That’s why he did this as soon as he spotted the Lakers charging back.

Nine players slowed down. The 10th was Anthony Davis. It’s not until Davis reaches the Blazers’ three-point line that he slowly turns around, takes a deep breath, and recharges to play defense. By then, it’s too late. Lillard’s already into his move, having fooled Davis into thinking he’d pursue a traditional fast break.

By the end of the play, it looks like Davis’ mistake was employing drop coverage. But was it really? Or was it more that Lillard recognized that Davis was in a vulnerable position from the previous play and exploited it? Wasn’t it more that Davis got caught … scrambling?

Basketball’s not football. It’s not a start-and-stop game where you can huddle up between every play to review the plan. It flows from one sequence to another, and everything that already happened in the game weighs on the players’ minds. In those split seconds, the line between each type of pick-and-roll coverage gets blurrier and blurrier. It does you a disservice when we try too hard to sharpen them retroactively.

There’s just one more thing …

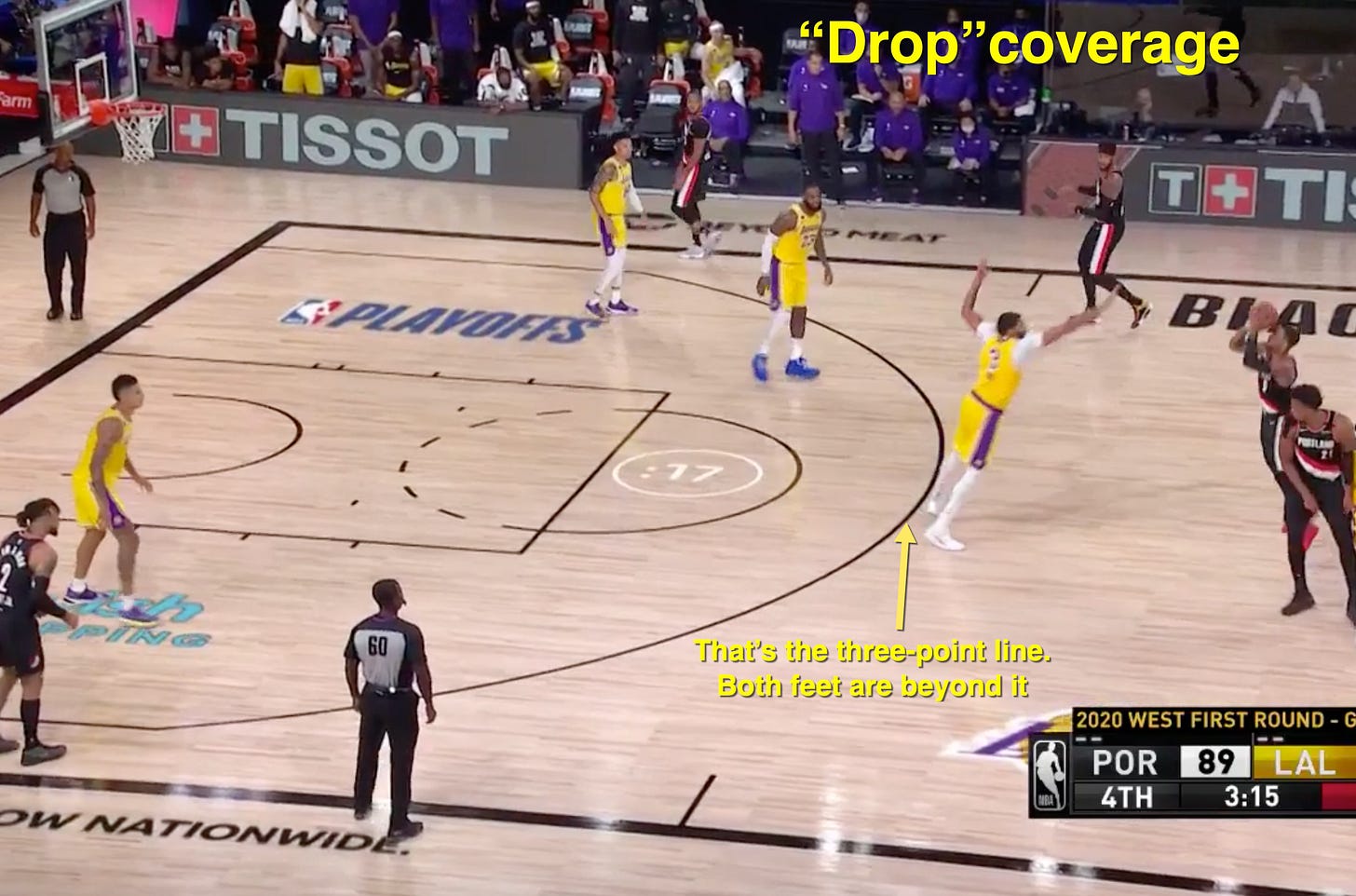

Can you believe that this looks like “drop” coverage?

Anthony Davis is two steps beyond the three-point line and is still 10 feet away from Lillard. Stop and think about that for a second!

We laugh at Paul George’s “bad shot” commentary on Lillard’s dagger to eliminate Oklahoma City last season. What a sore loser! My man got owned! I do it too. It’s funny!

But … he’s also kinda right. Before Lillard and Curry came along, could you imagine saying that a 35-foot stepback or a 38-foot pull-up is a good shot? Of course not! It would be completely absurd.

Yet we’ve arrived at that point because these pioneers are smashing through glass ceilings every single game. Davis is a seven-footer that’s out 25 feet beyond the hoop … and he’s catching strays for not being 10 feet further. Can you believe that?

I get it, man, but the playoffs are hard,” you might say. “You gotta do what needs to be done.” To that, I say: yeah, OK, I guess. But if the Lakers really want to win Game 2, they’re better off focusing on an offense that scored 37 second-half points against the worst defense in the bubble than their pick-and-roll coverage against Lillard’s logo shots.

Otherwise, they’ll be victimized by the most dangerous superpower of any transcendent player: the ability to induce the kind of mass panic that turns a No. 1 seed into something completely unrecognizable.