This’ll be the last newsletter piece for a couple weeks. Our second child (a boy) is coming imminently and I’m going to take a couple weeks to focus on being a dad. In the meantime, I wrote a piece for Complex on NBA TV ratings and why the solution is for the league to sell the beauty of the actual game again. Check that out here.

The 2020-21 NBA season will begin around 19 months since Kevin Durant last took an NBA floor. That, of course, was when KD crumbled to the floor early in the second quarter of Game 5 of the 2019 NBA Finals.

More to the point, it will be close to 21 months since Durant made his case as the best player in the sport with a 50 spot in the Game 6 clincher against the Los Angeles Clippers. The highlights underscore what we’ve always known about KD: he makes the game look so goddamn easy. You wonder why the Clippers even bothered to defend him at all.

That was one of our last snapshots of Kevin Durant as an actual basketball player instead of a lightning rod. Given everything else swirling around Durant in the spring of 2020, it was, to be honest, easy to forget his status as a superstar at the absolute top of his craft.

Two months later, KD suffered the game’s most debilitating injury, having rushed back from another injury to jump straight into an NBA Finals elimination game. Given the events of the sport and the world since, the memory of Durant as an actual basketball player is dimmer than ever. It’s been easy to forget how easy he made the sport look.

But that was the pre-Achilles tear version of Kevin Durant. How will the post-Achilles Tear version play? Will he make the game look as easy as he once did, just with a new team? Will he have to reinvent himself to stay among the league’s elite?

I’m not a doctor, and I’m certainly not a fortune teller. I want to see that old KD again and thus may be engaging in some motivated reasoning. I have many questions about KD’s new roster, his rookie head coach, and most notably, his self-selected co-pilot.

But I’m actually quite optimistic about Kevin Durant as an individual basketball player. Here’s why I’m confident he will at least resemble his old self.

Margin for error

What made Kevin Durant such an unstoppable offensive player before his Achilles tear? The simple answer is, well, simple: he is lethal from almost every spot on the court. He’s great at shooting threes off the catch, threes off the dribble, mid-range jumpers, layups, floaters, turnarounds, one-legged fadeaways, stepbacks, rise-ups, dunks, scoop shots, wrong-footed finishes, bullshit like this … the list goes on.

Here are his shooting percentages by zone during his career, courtesy of Cleaning the Glass. The number next to the percentages refers to his percentile rank among players at his position. Orange is high. Blue is low. Look at all that orange!

Outside of that bizarrely low number next to his corner three-point percentage in his last healthy season, KD has ranked in the top half at his position in shooting accuracy from every zone since 2012-13. That’s 47 out of 48 zones! This despite maintaining one of the highest usage rates in the league and shooting a ton of heavily contested shots. He’s not just sneaking over average, either — he’s above the 85th percentile most of the time and only twice dipped below the 70th.

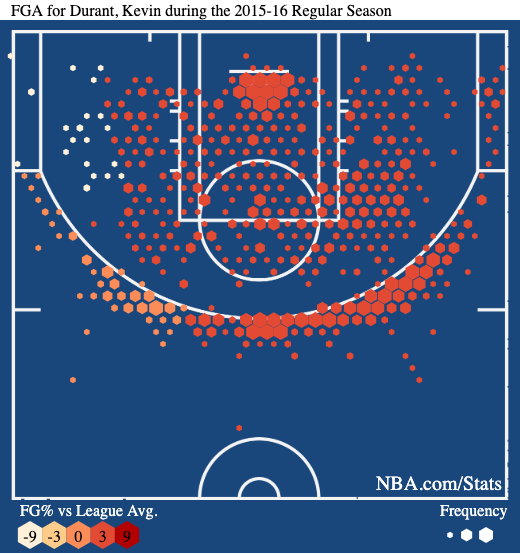

That wide-ranging accuracy was also compiled on both sides of the court. Here are some shot charts from past seasons, per the NBA’s stats page. The redder the dot, the better he shot relative to league average. The bigger the dot, the more often he took that specific shot. There’s red everywhere.

Those buckets come off so many different types of movement patterns. His assisted/unassisted ratio on his field goals has been within a 55-45 percent range in either direction in seven of the last eight seasons. (The lone exception was his first year in Golden State, when 61.7 percent of his hoops were assisted). The assisted hoops are an even mix of spot-ups, pindowns, cuts, and turnarounds in the mid-post. The unassisted ones come from all different foot and ball positions. He doesn’t even need to square his feet to the rim.

He’s most lethal pulling up to his left.

But he can also sidestep to his right.

Or rise up off two feet.

Or shoot runners off his inside foot.

Or outside foot.

So Kevin Durant’s a good basketball player. Thanks, Captain Obvious.

The larger point — which may seem equally obvious but is actually essential — is that KD is a remarkably versatile scorer. He doesn’t really have a single sweet spot or pet move that relies heavily on a single body part, even one as important as an Achilles tendon. If one element of KD’s offensive game is adversely affected by the injury, he has many others to fall back on.

Playing on a surgically repaired Achilles tendon will undoubtedly have some effect on his shooting. You need legs to shoot and you need feet to jump. The Achilles tendon connects those two bodily functions. You don’t have to be a doctor to get that.

Still, KD is starting from such a high level that he should still be one of the game’s best shooters even if he loses, say, 10-15 percent of its effectiveness from each zone while getting slightly fewer shots off. An above-average shooter from everywhere may not be as good as the very best shooter from everywhere, but they’re still pretty damn good. Just ask Khris Middleton.

Better yet, ask, Breanna Stewart, the Seattle Storm star and close KD friend who ruptured her right Achilles tendon less than a year earlier. Compared to her 2018 MVP campaign, Stewart was about 10-15 percent less effective as a shooter across the board in 2020.

Her overall shooting accuracy fell from 52.9 to 45.1 (14.8 percent drop)

Her effective field goal mark dropped from 58.9 to 51. (13.5 percent drop)

Her true shooting went from 63.3 to 57.8. (9.2 percent drop)

Her three-point shooting tumbled from 41.5 to 36.8 (11.4 percent drop)

Her two-point shooting skidded from 57.6 to 49 (14.9 percent drop)

In this way at least, she was about 85-90 percent the player she once was. That still made her one of the best players in the sport, if not the best, and the unquestioned best player in the postseason. Not bad.

There are all sorts of reasons for that, of course. They range from the overseas ball she already played, the absence of other key WNBA stars, the kind shooting environment of the Wubble, and even physiological differences between genders. (From what I’ve read at least, men are much more likely to suffer Achilles ruptures than women because their tendons are longer and skinnier. There’s some thought that women also recover faster than men, but those studies have been inconclusive). Stewart was also younger than Durant when she got hurt.

But the important point is that she still felt like Breanna Stewart to her opponents, both in terms of production and reputation. She still was an above-average marks(wo)man from each zone, and opponents treated her as such. I see no reason why an 85-90 percent version of Kevin Durant will feel like something other than Kevin Durant to his opponents, even if he’s not making quite as many of those shots. As long as he still has those occasional barrages, his image will persist and his opponents will defend his reputational strengths in such a way that’ll open up the rest of his game.

That assumes we’re only getting 85 percent of the old Kevin Durant next season. What if that’s overly pessimistic?

Let’s “dip” into some biomechanics

How does KD shoot and make so many types of jump shots? Well, he’s really tall and has really long arms. Nobody can block his shot, ergo he gets a clean look every time from every spot. Simple, right?

Not exactly. It’s true that KD’s release point is too high for anyone to reach. It’s also true that his speed and agility lets him escape taller defenders as easily as he lofts shots over smaller ones.

But the key to Kevin Durant’s shot versatility isn’t that high release point. It’s his size combined with the speed and fluidity of his shooting motion. He doesn’t just shoot higher than his opponents can jump. He shoots higher and significantly faster, all because he has one of the best dips in the NBA.

What’s a “dip.” The best way to think of it is as a a simple up-down motion that every single shooter uses to add rhythm to their jump shot, whether they notice it or not. Your body naturally dips whenever you bend your knees to shoot, which is always if you are doing it correctly.

What are your arms doing during this crucial moment in the shot? For a while, coaches taught their players to keep them up at the point of release, even while their knees dropped down. Some still do, for some reason.

It doesn’t take long to realize why that’s horrible, misguided advice. Step away from the computer, bend your knees, and jump in the air. Pay attention to your arms. Does it feel natural to leave them above your shoulders as you drop your knees? Are you even strong enough to keep them up there in the first place?

Say you are. How high are you able to jump while keeping them raised? Now, try loosening your arms and letting them swing with your body’s momentum. Better yet, try actively dropping them when you bend your knees and swooping them up as you leave your feet.

Do you jump higher? Does it feel more natural? Of course it does. Try it. You’ll see. So why would you ever try to control your arms during a jump? You’re working against your body’s natural upward trajectory.

The same principle applies with jump shooting. It’s a multi-layered motion that requires balance and coordination throughout the body. If any part of the body is working against another, it throws off the shot’s entire rhythm and power. You won’t be able to jump high, much less toss a basketball anywhere near a spherical ring from very far away. And that’s without any defenders trying to stop you.

That’s why every single player in the sport keeps their arms loose, allowing them to come down to their lower body and then uncoil into an upward motion. This motion is known as the “dip.” It’s how every player generates the power necessary to shoot from long range and the body rhythm to do so accurately against five roaming sets of arms and hands. The more the sport has moved to the perimeter, the more essential the dip has become.

Kevin Durant is no exception. Watch for the dip in these shots. You might miss it if you don’t look closely, but it’s there. Watch for the up and down motion once he catches the ball.

It’s easy to see those shots at full speed and take for granted that Kevin Durant is really tall, with long arms and an elongated torso. He releases the ball around his forehead, which is at least 11 feet in the air by the time he reaches the apex of his jump.

That’s a lot of room for that dip to lose its rhythm with the rest of the body, especially when trying to shoot quickly to beat athletic closeouts. Watch Giannis Antetokounmpo’s choppy motion to see an example of one’s size working against them when shooting jumpers.

Yet Durant’s dip is loose and fluid despite his size. He drops his arms to his shooting pocket and then back up to his head so easily, from almost any angle, on every shot. It doesn’t matter whether the pass is low, high, straight, or crooked. Nor does it matter if he’s pulling up off the dribble or shooting from deep. The ball goes down to his waist and then back up to his head in an instant.

No interruptions, no buffering. It’s like a website that loads instantly.

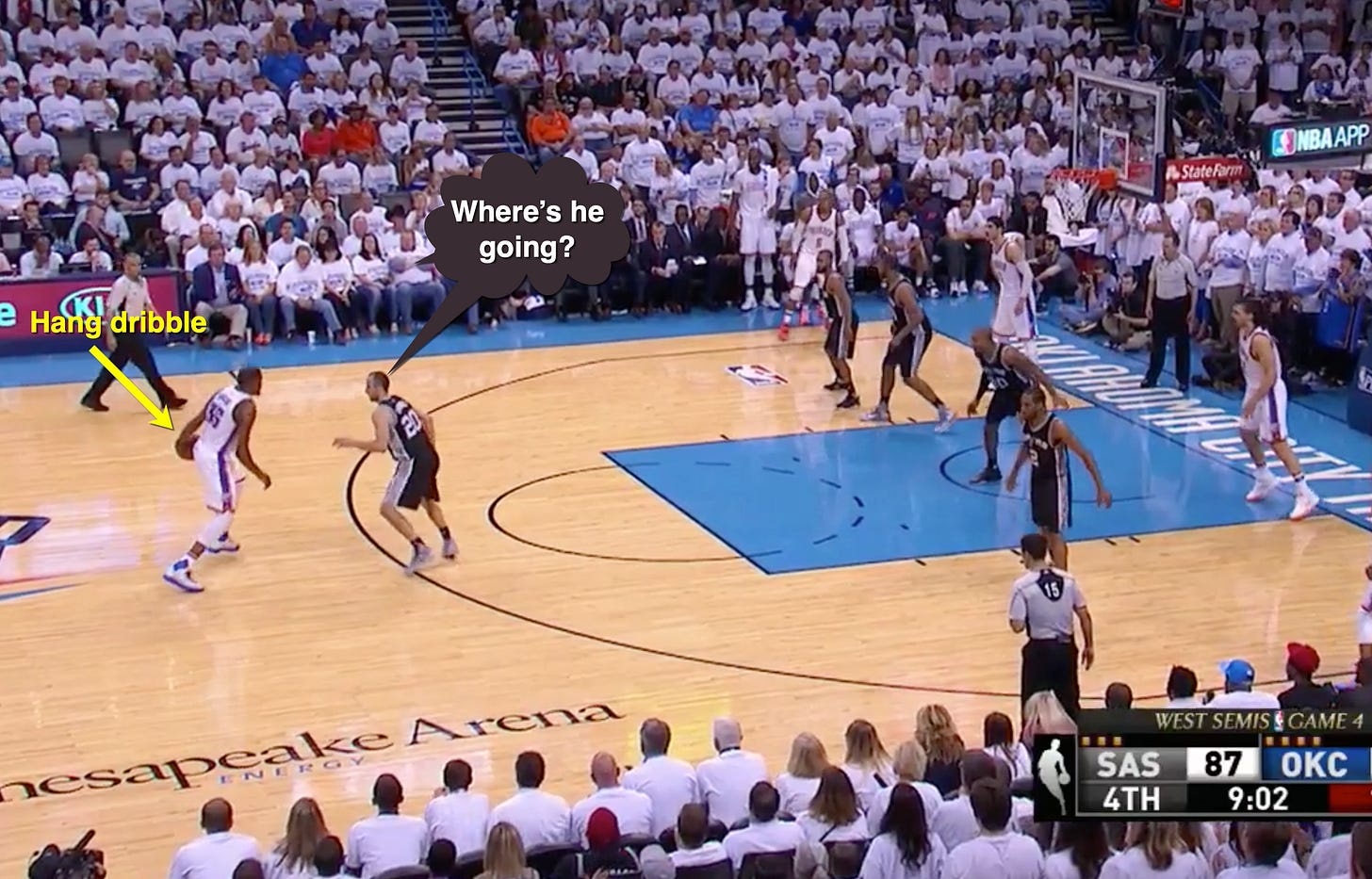

The same thing happens when shooting off the dribble. KD loves to let the ball hang up to his upper thigh and then snatch it there to go right into his shot. Most players can’t do this as effectively because they’d be bending down lower than usual to then accelerate up. Not KD. Because he naturally dips to his torso on catch-and-shoot situations, the high dribble essentially becomes his dip. Before the defense knows it, KD has accelerated his arms up to his head to shoot in rhythm.

The speed and efficiency of that dip is the real reason KD always seems open when he shoots. Freeze the frame at the apex of the jump, and it can appear like the defender has a hand in his face and only misses the ball because KD is really tall. But that’s like judging a successful house remodel by the color of the paint on the walls. KD’s dip is the foundation of his shot, and it’s already done 90 percent of the work before the defender can even blink.

What does any of this have to do with a damaged Achilles tendon?

Consider the distance KD somehow covers so fluidly when bringing the ball from his torso to his head. That arm motion creates a ton of power and precision independent of what happens below the waist. As long as KD still gets the ball down to his shooting pocket and back up above his head like he once did, he should be able to rise and fire accurately while altering his leg positions to better account for any leftover weakness in his right Achilles.

That’s not the same thing as saying Durant’s shot is all upper body. Even he needs his legs to shoot, and those legs need sound feet with strong Achilles tendons to maintain his motion’s delicate balance. But he doesn’t need to use his legs as much for power as most shooters. He gets plenty with his arm dip alone.

That matters because Durant may have more trouble pushing off his right leg than before, both in the short and long term. Most players today hop slightly when catching the ball to quickly generate the body acceleration necessary to get long shots off. It gives them a head start, especially when shooting on the move. Breanna Stewart, for example, is a regular “hopper.” That’s how she gets her shots off so quickly from many different ranges.

Every time a player hops, they are leaving their feet, landing on their mid-foot, and then leap much higher in the air again. The Achilles tendon is crucial to that movement pattern because it’s the mechanism by which the energy from the hop transfers up the body. The weaker it is, the more difficult it is to land on balance and immediately jump again.

That’s one reason why Stewart’s shooting percentages went down from every zone this season. Her hops were about 85 percent as stable with a surgically repaired Achilles tendon as they were before.

Stewart must accept that shortcoming if she wants to play the same way she once did. Like 99.9 percent of pros, she needs to hop to generate enough power to maintain her shooting range and accuracy. Her arm dip can’t do it on its own. It’s not fast enough and her torso isn’t quite long enough.

Durant. though, has a fast enough arm dip and long enough, or at least as close to both as any player gets today. He is in the 0.1-percent class of player who can create a strong, elastic, versatile, and accurate shooting motion using (mostly) his arms and torso.

By this logic, his feet, while still important, are less essential to his shot than his peers. If that’s the case, then a reconstructed Achilles tendon should have less of an effect on his shot than it did on Stewart’s. Thus, he should not see his percentages drop as much as Stewart’s did.

That has major implications for the rest of his game

There’s no doubt that Kevin Durant will be less explosive on his drives after his Achilles tear. It will be harder for him to cut sharply off his right leg and then immediately power up to go hard to the basket off that foot.

Don’t be alarmed. Kevin Durant will still be able drive, finish creatively around the rim, and surge past a defender with his first step. The exclamation points on the end of his moves may be more muted, but I think the moves themselves will be juuuust fine.

Remember, the scariest part of KD’s offensive game is his ability to fire from anywhere at any time. Assuming he maintains that smooth arm dip, he will still be a lethal pull-up shooter. If he’s still a lethal pull-up shooter, he can use the threat of his jumper to get defenders off-balanced and drive by them. Maybe he’s 85 percent as quick when planting with his right leg in those situations, but that should still be enough to get his shoulders in front of the defender.

Here’s how that might work in practice.

Pre-Achilles tear, that play ended in a dunk. Post-Achilles tear, it might be a pull-up jumper, floater, or more of a finesse layup where he wrong-foots Green at the end. No, those aren’t dunks. But he’s pretty good at all of those shots, too.

The most important thing is that hesitation move at the beginning, sometimes known as the “hang dribble.” KD borrowed it from Tracy McGrady, another oversized wing superstar who used it to great effect to disguise his shoot-or-drive intentions. (Read all about that here). It’s like a pitcher who uses the same windup and arm angle for his fastball and change-up.

KD’s hang dribble is even more lethal than McGrady’s because it connects more naturally to his jumper’s biomechanics. McGrady needed to arch his body to create separation, which made him a more inconsistent shooter in the short term while screwing up his body over the long haul.

KD’s pull-up, on the other hand, is straight up and down. He’s shrunk the time between the snatch and the dip to almost zero, combining them into one single motion.

That makes it even easier to disguise his shoot-or-drive intentions. He snatches the ball to drive at the exact same point he yanks it back to shoot.

To see this in action, let’s rewind to Game 3 of the 2018 NBA Finals, one of KD’s signature playoff moments. One of these screenshots is from the famous pull-up three he made to put the game away. The other is from a drive earlier in the game. Can you guess which is which?

The first one is the drive. The second one is the long shot. But you had to think for a sec, didn’t you? The setup motion looks remarkably similar.

That deception will go a long way to overcome any slippage when exploding off the right foot. As long as he still can use the hang dribble to this effect, he should be able to create the initial advantage against his primary defenders.

By the way, KD doesn’t need to keep going the same way after that hang dribble. His crossover after it is equally devastating.

A surgically repaired Achilles will affect the end of some drives, at least initially. KD will have slightly more trouble veering back to keep the defender on his hip. Dunks might turn into layups, layups into runners, runners into swing-through fouls, and swing-through fouls into pull-up jumpers. Those weaving Eurostep moves to slice through help defenders will weave a bit less tightly. His shot attempts and shooting percentage in the restricted area should drop.

But as long as he still has the threat of his pull-up jumper, he still has that hang dribble to build off it. And as long as he has the hang dribble, he still has the primary mechanism he always used to create the initial separation needed to get shots off.

There’s one more thing

Suppose, for the sake of argument, that Kevin Durant’s surgically repaired Achilles isn’t strong enough to maintain much of his face-up game. Maybe it’ll affect the speed and fluidity of his arm dip more than I expect. Maybe it’ll blow a flat tire when trying to explode off the hang dribble. Maybe he can’t be a 7’0 perimeter player anymore.

I strongly doubt any of that happens. But even if it does, KD can still do this.

Defenders could once push KD out when he tried to go to the mid-post, but that changed over the last few seasons as KD developed more core strength and some clever tricks with his feet. Once he catches the ball with you on his back, it’s over. He’s even developed the one-legged fadeaway that was Dirk Nowitzki’s trademark.

(Did you notice how KD pushes off his left foot on that move? Remember, KD ruptured his right Achilles, not his left).

So if all else fails — if he somehow cannot play on the perimeter at all anymore for whatever reason — KD can still wedge his way into post position and shoot over any defender. That’s a nice fallback option.

But I don’t think it’ll come to that

I know the history of this devastating injury. I know that KD is closer to the end of his prime than the beginning. I know he’s playing on a new team that’s a big ol’ mystery box. Nobody is ever exactly the same after tearing their Achilles. But I feel confident that Kevin Durant will be pretty damn close.

In addition to all the unique factors of his game we covered, KD will have the advantage of those 19 (or so) months since his last game. He was able to take things slow and rest a body that went through multiple deep playoff runs prior to the injury. He will be fresh, which could be especially important next year if the owners get their desired pre-Christmas start.

Assuming he’s been diligent with his recovery, he will have taken that extra time to fix any other structural inequities in his body. I found it interesting that Stewart, in a revealing conversation with KD and Kelsey Plum about their Achilles recoveries, said her body felt better than ever after recovering from the worst injury a basketball player can have. Slowing down and really working on her entire body was in some way a blessing in disguise, something KD also echoed in the conversation. She needed the break. KD, for all sorts of reasons, did too.

Does that mean the best is yet to come for Kevin Durant?

I won’t go that far. But I also won’t rule it out.